If you are building a small college project, a standard database (like MySQL or PostgreSQL) is all you need. But what happens when you have over a billion daily active users?

At that scale, "one-in-a-million" bugs happen thousands of times a day. Hard drives become too slow. Networks get clogged. Entire clusters fail.

This is the story of how Facebook took a simple open-source tool - Memcached - and engineered it into a distributed beast capable of handling billions of requests per second. Based on their famous NSDI '13 paper, here is a look inside the architecture that keeps your timeline loading instantly. Read the original research paper.

The Core Concept: The "Look-Aside" Cache

Before we dive into the crazy scaling hacks, we need to understand the baseline. Facebook uses Memcache as a demand-filled look-aside cache.

Here is the flow:

Read: When a web server needs data (e.g., "Get Profile Picture"), it asks Memcache first.

Write: When data changes, the web server updates the database first. Then, it sends a delete request to Memcache to remove the old, stale data.

Why delete instead of update? Because "deletes" are idempotent. If you accidentally send a delete command twice, the result is the same (the data is gone). If you sent an "update" command twice in the wrong order, you could permanently corrupt the cache with old data.

This sounds simple. But when you scale this to thousands of servers, things break in spectacular ways.

Challenge 1: The "Thundering Herd"

Imagine a celebrity posts a new photo. It is cached in Memcache, and millions of people are viewing it. Suddenly, the cache entry expires or is deleted.

In that specific millisecond, the cache is empty.

User 1 checks cache Miss Goes to Database.

User 2 checks cache Miss Goes to Database.

User 10,000 checks cache Miss Goes to Database.

This is called a Thundering Herd. Thousands of requests slam the database simultaneously for the exact same key, potentially crashing the database.

The Solution: Leases (The "Ticket" System)

Facebook solved this by introducing Leases.

Now, when the cache returns a "Miss," it attaches a Lease Token (a 64-bit ID). It essentially tells the web server: "Okay, the data is missing. YOU are the chosen one. You have the ticket to go to the database and refill the cache."

If other users ask for the same key while the first user is busy, Memcache tells them to wait for a few milliseconds.

The Result: In a test of high-traffic keys, this reduced the peak database query rate from 17,000/sec to just 1,300/sec.

Challenge 2: The "Gutter" (Handling Failure)

In distributed systems, machines die all the time. If a Memcache server fails, you lose that portion of the cache.

The naive solution is to just re-route those requests to the remaining live servers. This is dangerous. If one server fails because it was overloaded, shifting its traffic to other servers might overload them too. This causes a cascading failure - the servers fall like dominoes.

The Solution: Gutter Servers

Facebook set aside a small pool of idle machines (about 1% of the fleet) called the Gutter.

When a client doesn't get a response from a main Memcache server, it doesn't bother the other main servers. Instead, it sends the request to the Gutter.

If the Gutter misses, the client fetches from the DB and puts the data in the Gutter.

Entries in the Gutter expire very quickly to keep things fresh.

The Gutter acts as a "spare tire," protecting the database from the sudden flood of traffic caused by a server failure.

Challenge 3: Invalidation at Scale (McSqueal)

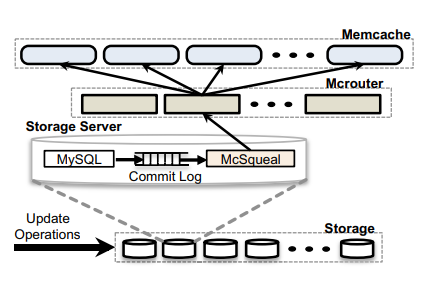

As Facebook grew, they split their infrastructure into Regions. A region contains a Storage Cluster (the master database) and multiple Frontend Clusters (web servers + Memcache).

When data changes in the database, you have to tell all the Frontend Clusters to delete their old cached copies. If web servers tried to broadcast these deletes themselves, it would create a massive packet storm, clogging the network.

The Solution: McSqueal

They built a daemon called McSqueal that runs on every database server.

This batching resulted in an 18x improvement in efficiency.

Challenge 4: Global Consistency (The Speed of Light)

Finally, let's go global. Facebook has regions in the US, Europe, and Asia.

One region is the Master (where writes happen).

There is a delay (lag) when copying data from the Master to the Replicas.

The Nightmare Scenario:

The Solution: Remote Markers

To fix this, Facebook uses Remote Markers.

When a web server updates data:

Now, if the user refreshes the page:

This ensures the user always sees their own changes instantly, even if the database is lagging behind.

Key Takeaways

Latency over Consistency: Facebook often chooses to show slightly stale data to keep the site fast, but they have clever mechanisms (like Remote Markers) to hide this from the user when it matters.

Stateless Clients: They kept the Memcache servers "dumb" and simple. All the complex logic (Leases, Gutter routing) lives in the client software on the web servers.

UDP vs. TCP: They use UDP for "Get" requests because it's faster and cheaper. If a packet drops, they just treat it as a cache miss. They only use TCP for "Sets" and "Deletes" where reliability is required.

Scaling isn't just about buying more servers; it's about predicting where the bottlenecks will move next. Whether it's the thundering herd or the speed of light, Facebook's architecture shows that at scale, you have to engineer your way around the laws of physics.